I Am You by Member of the Restorative Justice Project and Mural Arts Program, Sci Graterford

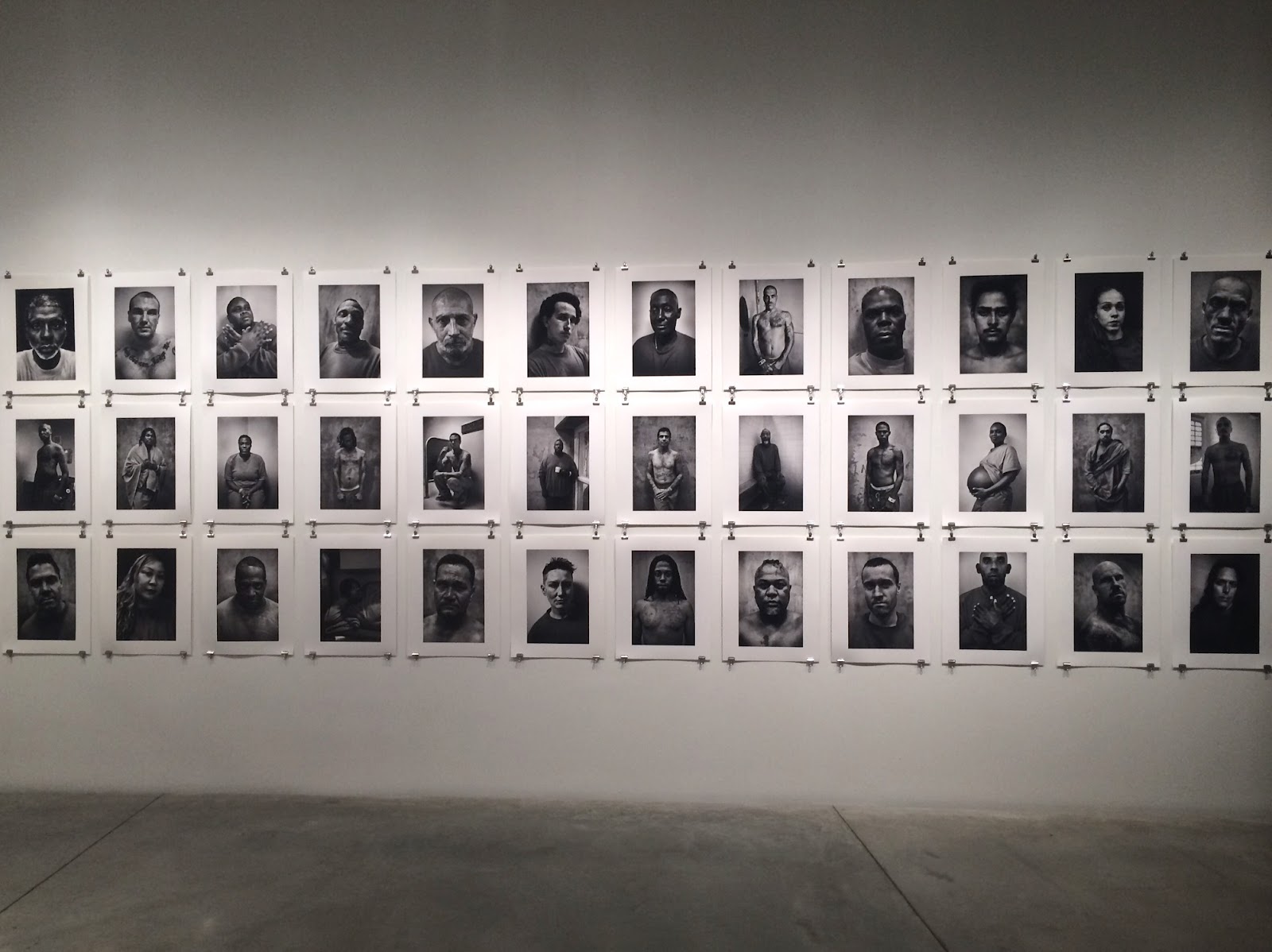

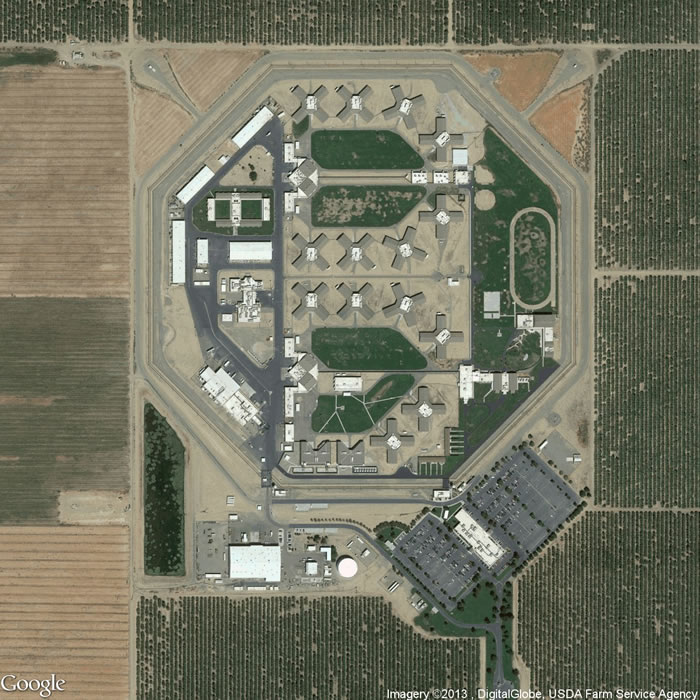

Even if you watch Orange is the New Black religiously, chances are your encounters with everyday prison life are limited. Even cursory image searches for "US prisons" and "prison industrial complex" result in a disportionate amount of caricatures and stock photography, versus actual snapshots of what life is like for millions all over the world. Freelance writer and curator Pete Brook, the founder of the Prison Photography blog, would argue that the distance between society and prison life is problematic. In order to investigate what he calls “the culture of incarceration,” he's bringing traveling exhibition, Prison Obscura, to the Sheila Johnson Design Center at the Parsons School of Design in New York City.Brook’s curatorial eye seeks to personify the silenced and invisible. In the show, three cubelike structures made of wood and bright orange bars hint at the the dimensions of a prison cell while providing spatial relationships between and depth to the pieces in the show. Comprising nine different artists and projects, the exhibition both looks critically at prisons, humanizing those who have been put inside of them. Individual artworks explore ideas including, who holds the camera when we see the unseen? Is it a photographer visiting prisons for nine years, like Robert Gumpert, who captured stunning high contrast images of inmates in his Take a Picture, Tell a Story series? It is Google Maps, which Josh Begley used to view prisons for his Prison Map project? Is it young inmates themselves, taking pictures of each other with cameras and photography workshops provided by Steve Davis? Or is it held in the digital world, like in Proliferation, Paul Rucker’s exploration into prisons over time? The exhibition probes and examines the different ways in which viewers can look in on the worlds of the incarcerated.The Creators Project spoke with Pete Brook about Prison Obscura and the future of the Prison Photography blog:Proliferation, 2010 by Paul RuckerThe Creators Project: Was there a specific moment that you became interested in prison photography? How long after did you decide to start the Prison Photography blog?Pete Brook: I did an M.A. in Museum Studies. I looked at the San Quentin Prison Museum. In order to evaluate the museum’s narrative, I had to read up on California prison politics. This was 2004 and things were really bad. I was gobsmacked when I learned how deep the problems went. In my lifetime, the U.S. prison population had grown fivefold—seemingly without any checks and balances.I started Prison Photography in late 2008. It attracted most of its modest early attention within the small photo blogosphere. I’d been bookmarking projects since 2006. I didn’t really have a plan but I knew most of the projects I’d identified hadn’t had a second outing since their first publications and none of it had been brought together in one place. I was excited to just start piecing it together in public. If people wanted to read along, then Bonus!I’m talking about photography, but really, I’m talking about prisons. And when I’m talking about prisons, I’m really talking about society. Prisons are a symptom of other failures in society—failures to provide good schools and job opportunities; failures to stymie the growing wealth gap; failures to treat addiction; so on and so forth. Taxpayers are bearing the cost for prisons, so they should be demanding to know what’s happening behind the walls. Sometimes photography can illuminate that.

Individual artworks explore ideas including, who holds the camera when we see the unseen? Is it a photographer visiting prisons for nine years, like Robert Gumpert, who captured stunning high contrast images of inmates in his Take a Picture, Tell a Story series? It is Google Maps, which Josh Begley used to view prisons for his Prison Map project? Is it young inmates themselves, taking pictures of each other with cameras and photography workshops provided by Steve Davis? Or is it held in the digital world, like in Proliferation, Paul Rucker’s exploration into prisons over time? The exhibition probes and examines the different ways in which viewers can look in on the worlds of the incarcerated.The Creators Project spoke with Pete Brook about Prison Obscura and the future of the Prison Photography blog:Proliferation, 2010 by Paul RuckerThe Creators Project: Was there a specific moment that you became interested in prison photography? How long after did you decide to start the Prison Photography blog?Pete Brook: I did an M.A. in Museum Studies. I looked at the San Quentin Prison Museum. In order to evaluate the museum’s narrative, I had to read up on California prison politics. This was 2004 and things were really bad. I was gobsmacked when I learned how deep the problems went. In my lifetime, the U.S. prison population had grown fivefold—seemingly without any checks and balances.I started Prison Photography in late 2008. It attracted most of its modest early attention within the small photo blogosphere. I’d been bookmarking projects since 2006. I didn’t really have a plan but I knew most of the projects I’d identified hadn’t had a second outing since their first publications and none of it had been brought together in one place. I was excited to just start piecing it together in public. If people wanted to read along, then Bonus!I’m talking about photography, but really, I’m talking about prisons. And when I’m talking about prisons, I’m really talking about society. Prisons are a symptom of other failures in society—failures to provide good schools and job opportunities; failures to stymie the growing wealth gap; failures to treat addiction; so on and so forth. Taxpayers are bearing the cost for prisons, so they should be demanding to know what’s happening behind the walls. Sometimes photography can illuminate that.

Where did the idea for curating the Prison Obscura exhibition originate?I was invited by Haverford College to curate. Exhibitions Coordinator Matthew Callinan asked, “Is there an exhibition format for the work on the website?” The timing was perfect. I’d been at it five years and knew some materials deserved gallery presentation and that my ideas needed to be tested by a different type of public outing.Parsons is the fourth venue for Prison Obscura.

Where did the idea for curating the Prison Obscura exhibition originate?I was invited by Haverford College to curate. Exhibitions Coordinator Matthew Callinan asked, “Is there an exhibition format for the work on the website?” The timing was perfect. I’d been at it five years and knew some materials deserved gallery presentation and that my ideas needed to be tested by a different type of public outing.Parsons is the fourth venue for Prison Obscura.

Did you have a motive or a desired outcome for this exhibition?I want us to stop thinking that prison issues are in any way radical. We’ve got 1 in every 100 adults behind bars. Prisons are, unfortunately, central to American identity. We must disavow the notion that prisoners are in anyway different to us. Often photography has served to maintain or deepen the “Othering” of prisoners. I want the Prison Obscura audience to question what photography does. I want to showcase artistic practices that are respectful to prisoners, illuminating to all others and actually empower all involved—practices that are replicable and of good conscience.I hope people are informed. I hope Prison Obscura gives folks the starting point to discuss these expressing issues at the dinner table and with friends. It starts there. Then, I hope people take it with them to the ballot box. It is my small contribution to a growing shift toward more sensible debate about punishment and policy in this country.

Did you have a motive or a desired outcome for this exhibition?I want us to stop thinking that prison issues are in any way radical. We’ve got 1 in every 100 adults behind bars. Prisons are, unfortunately, central to American identity. We must disavow the notion that prisoners are in anyway different to us. Often photography has served to maintain or deepen the “Othering” of prisoners. I want the Prison Obscura audience to question what photography does. I want to showcase artistic practices that are respectful to prisoners, illuminating to all others and actually empower all involved—practices that are replicable and of good conscience.I hope people are informed. I hope Prison Obscura gives folks the starting point to discuss these expressing issues at the dinner table and with friends. It starts there. Then, I hope people take it with them to the ballot box. It is my small contribution to a growing shift toward more sensible debate about punishment and policy in this country.

In your point of view, what is the biggest issue today in America’s prison industrial complex?There’s so many. Let’s stop putting people to death. It’s foolish and symbolic. That would only help a few thousand people, though—a drop in the bucket of the 2.3 million locked up. Let's stop trying youth as adults. Let’s stop shackling women in labor. Let’s give compassionate release to old men and women who need to be in infirmaries not prisons. Let’s treat drug addiction as a public health issue and not a criminal issue. Let’s release retroactively the hundreds of thousands of people who are locked up on non-violent crimes but have been sucked into mandatory minimum sentencing laws. California just downgraded the legal definition of many non-violent crimes from felony to misdemeanor. Other states can do the same. Three strikes is redundant at this point.Above all else, let us all admit together that prisons have not done and do not do what they claim to do. Prisons do not make us any safer. Prisons, for the most part do not rehabilitate or educate or train prisoners to a degree that we should expect. That is not to denigrate the hard efforts of prisoners to improve themselves, but merely to point out that most prisons are warehouses. We know that upwards of 90% of prisoners are getting out and yet we sentence them to years of boredom, sporadic violence, predation, petty rivalries and forced docility.

In your point of view, what is the biggest issue today in America’s prison industrial complex?There’s so many. Let’s stop putting people to death. It’s foolish and symbolic. That would only help a few thousand people, though—a drop in the bucket of the 2.3 million locked up. Let's stop trying youth as adults. Let’s stop shackling women in labor. Let’s give compassionate release to old men and women who need to be in infirmaries not prisons. Let’s treat drug addiction as a public health issue and not a criminal issue. Let’s release retroactively the hundreds of thousands of people who are locked up on non-violent crimes but have been sucked into mandatory minimum sentencing laws. California just downgraded the legal definition of many non-violent crimes from felony to misdemeanor. Other states can do the same. Three strikes is redundant at this point.Above all else, let us all admit together that prisons have not done and do not do what they claim to do. Prisons do not make us any safer. Prisons, for the most part do not rehabilitate or educate or train prisoners to a degree that we should expect. That is not to denigrate the hard efforts of prisoners to improve themselves, but merely to point out that most prisons are warehouses. We know that upwards of 90% of prisoners are getting out and yet we sentence them to years of boredom, sporadic violence, predation, petty rivalries and forced docility.

Have you ever been contacted by any outside authorities concerning your work?Little ol’ me? Never. I don’t think I’m a threat in anyway. Everything I do is done in public. I’m not making any claims that I can’t back up. Hell, if I was someone they needed to spend time on, we’d really be screwed!What is the future of Prison Photography?I’ve never had a plan. That continues to be the case. I’m not short of things to focus on. Prison Photography is always in-between my actual paid work though. The website has never paid the bills and it never will. That’s as it should be. It’s my side project that keeps me honest and sane. It has allowed me to travel and speak and make exhibitions. I’m a lucky fella.Currently, I’m doing a project whereby I’m crowdsourcing language used by prisons to instruct and motivate prisoners. There’s slogans and statements made in public areas of prisons, usually painted, that are incongruous at best, bizarre at worse. Such broad-stroke language which seems in some cases to be in denial of the nature of the space reveals carceral logic in a very soft way. As I’ve been bringing together images of prisons for years, I want to have a quick go at bringing together the vocabulary of prisons. This is in collaboration with ERNEST and art-collective from San Francisco that is working in residence at c:3 Initiative in Portland on a project about the mothballed Wapato Jail.I have a compulsion to blog regularly, so Prison Photography will live on. Indefinitely. ;)Prison Obscura is up at the Sheila Johnson Design Center until April 17. Stay updated with Brook’s Prison Photography blog here.Related:Ai Weiwei Takes Over Alcatraz For New ExhibitionRoss Manning Is Bringing Light To Tasmania's Old Convict CellsJR's Haunting Murals Invade Ellis Island

Have you ever been contacted by any outside authorities concerning your work?Little ol’ me? Never. I don’t think I’m a threat in anyway. Everything I do is done in public. I’m not making any claims that I can’t back up. Hell, if I was someone they needed to spend time on, we’d really be screwed!What is the future of Prison Photography?I’ve never had a plan. That continues to be the case. I’m not short of things to focus on. Prison Photography is always in-between my actual paid work though. The website has never paid the bills and it never will. That’s as it should be. It’s my side project that keeps me honest and sane. It has allowed me to travel and speak and make exhibitions. I’m a lucky fella.Currently, I’m doing a project whereby I’m crowdsourcing language used by prisons to instruct and motivate prisoners. There’s slogans and statements made in public areas of prisons, usually painted, that are incongruous at best, bizarre at worse. Such broad-stroke language which seems in some cases to be in denial of the nature of the space reveals carceral logic in a very soft way. As I’ve been bringing together images of prisons for years, I want to have a quick go at bringing together the vocabulary of prisons. This is in collaboration with ERNEST and art-collective from San Francisco that is working in residence at c:3 Initiative in Portland on a project about the mothballed Wapato Jail.I have a compulsion to blog regularly, so Prison Photography will live on. Indefinitely. ;)Prison Obscura is up at the Sheila Johnson Design Center until April 17. Stay updated with Brook’s Prison Photography blog here.Related:Ai Weiwei Takes Over Alcatraz For New ExhibitionRoss Manning Is Bringing Light To Tasmania's Old Convict CellsJR's Haunting Murals Invade Ellis Island

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement